I like folk music, or at least I like my idea of folk music.

Seeing Billy Bragg at around 18 was a formative experience for me. He was someone who had grown up a few towns away from me and sang with my accent. It made it seem like people who made records didn’t live on other planets.

His records had the words ‘file under urban folk’ written on them. It was a grand claim for someone who was clearly a punk artist. To me the word ‘folk’ conjured up something more exciting and wild then punk rock.

I settled on my own flawed definition of what the word ‘folk’ meant and from then on that this was the music I wanted to make. A modern, relevant style of narrative song-writing that could relate both the political and personal. Song composition that gave words and story the same importance as melody and sound.

I wanted to be clear and precise. I think it’s that total commitment to meaning that puts many people off folk music. Folk has no burry edges, it’s presented in sharp focus.

I’m aware of the idea that folk music should represent its time and be the music of the people. Mike Skinner of the Streets is a better folk artist then I’ll ever be.

There is also another folk stereotype, that of the dusty librarian. The folk musician who acts as a custodian of tradition and songs and believe they should never be abridged or altered. This in turn supports the myth that traditional folk is a closed club, only open to those that have memorised the repertoire.

It’s a reputation not without some foundation.

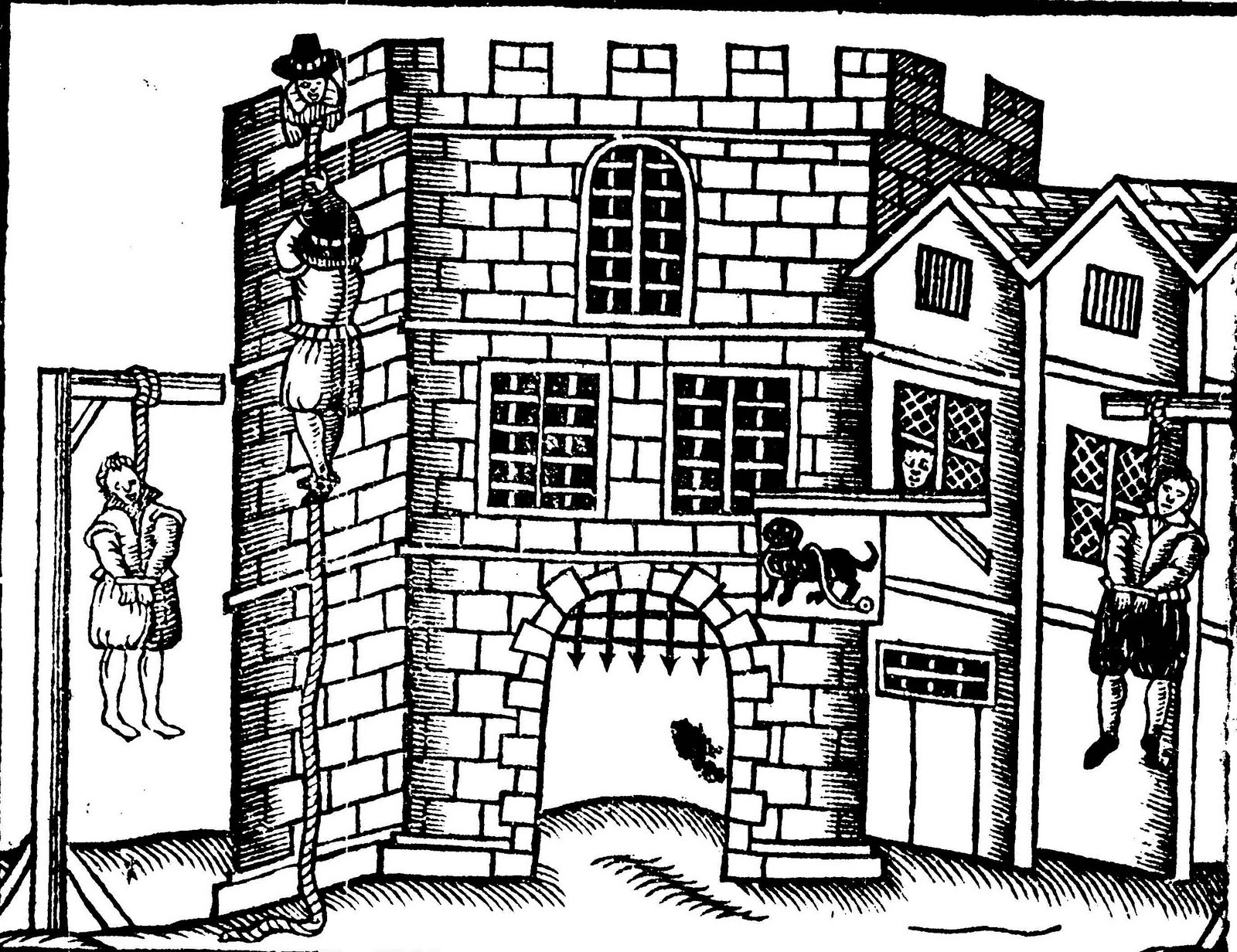

Last year I made a historical album the East Anglian Witch Trials which took place during the English Civil War called The Violence. It’s the first time I’ve attempted any project not set in modern times. I was making folk music for people who had been dead for centuries.

I knew I also had to look at the actual folk music of the time. The 17th Century bought about the birth of the printing press and consequently songs are better notated and preserved from this period.

At first the idea was to pepper the Violence with a few pieces of traditional music to create some historical context for the stories.

However the song research soon got legs of its own and The Violence had a sister project, a collection of 17th Century Folk Songs called Bugbears.

My main problem in making this album was to how to present these songs. I couldn’t perform the songs in a historically accurate way, I don’t have the skill, knowledge or audience for that. Songs had more uses back then, they were news letters, soap, operas, movies and plays. More than anything they were long, really long, with verse after verse of exposition.

Neither did I want to adapt or update the songs and radically re-arrange them for modern ears. It was about finding the emotional centre of the music. Excising words that felt awkward on my lips and finding sentiments that rang true. Several of the more political songs had easily identifiable sentiments once a few details were air brushed out. Ballads spoke of women ruined by drink and young maidens seduced and tricked by conmen. I only changed a few nouns and it was a night out at All Bar One.

When researching the songs at the Cecil Sharp House I was helped greatly by the greatly respected song librarian Malcolm Taylor. It was with trepidation that I told Malcolm of my attention to shorten, edit and even add electric guitars and synthesis. Malcolm said it was wrong for me to think of the folk scene as resistent to that kind of change that the music should be allowed to adapt and grow.

I wanted to make these versions a bridges to the originals. Not facsimiles but echoes. I hope you like them.

It’s what I think of as Folk Music.