Tag: bugbears

The Shock of the Old

Darren Hayman and & Short Parliament’s album Bugbears is a rare thing. It’s a vision of the 17th century, and particularly the civil wars that saw Britain turned upside down; but it’s done through music that, though it’s more-or-less folky, is not at all nostalgic. Modern folk and 17th century history: it could be a little offputting. Putting aside the question of folk music, why would anyone be interested in the 17th century?

Here are three reasons, three things that everyone should know about Britain during those times:

1.

There was an information revolution. Really this began in mainland Europe with Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type in the middle of the 15th century, which revolutionised printing. But in Britain it happened between the late 16th and 17th centuries. What happened? New communication media — cheap print — opened up new kinds of dialogues, speeding up communication, making great swathes of information that had previously been the preserve of educated elites available to a much broader public. At the same time many people worried about these new media: would they disrupt old ways of learning and traditional values? Would they undermine knowledge as much as they spread it? How could you know whether something in these new media was true?

Does any of this sound familiar?

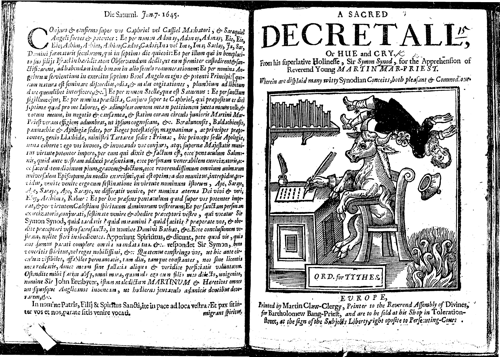

Cheap print was in some ways the equivalent of the internet. It seemed exciting and threatening at the same time. In Britain pamphlets began to appear — short books that argued about politics and religion in popular, accessible writing. They were intended to change what the reading public thought about things. Governments were concerned about the way pamphlets and pamphleteering might turn the world upside down, and from time to time tried to quash them. Pamphlets could not only be read by cobblers and tinkers: they could be written by them (actually the few who were literate). Gradually, however, politicians and governments accepted that pamphlets couldn’t be eradicated entirely, and increasingly they became part of the conduct of ordinary, everyday politics. If you wanted people to take your side, you persuaded them through print.

Pamphlets were like blogs: pithy statements of fact and opinion, arguments with invisible enemies that sewed new ideas, explorations of popular religion that were not controlled or authorised by the church. Writers didn’t care who their anonymous readers were: this was a very public, perhaps democratic, form of engagement. With a pamphlet you could try to persuade people to take your side in an already polarised conflict; or you could just throw an idea out there and see if it floated. When the civil wars began — in 1637 or 1642 depending on how you look at it — pamphlets were part of the warfare. They were paper bullets.

Meanwhile weekly newspapers (which appeared in 1641) speeded up the news, and made more news accessible to more people. In a way they created the first news cycle (at least in Britain), because readers expected weekly updates. These days we have our 24 hour news cycle. In the 17th century the news was weekly: but this in itself was quite revolutionary, and perhaps changed the way people thought of time and history, exactly as it was happening around them. This was a media revolution.

2.

As the extraordinary The Violence records at double-album length, 17th century British people believed in witches — believed in them enough to hang a few hundred poor, defenseless old women. Surely this has to be the apogee of superstition?

But there was another aspect to 17th century Britain, one that we would call ‘modern’. These are some of the things that happened in 17th century Britain: the introduction of coffee, tea and drinking chocolate; the introduction of coffee houses, where you could drink a cup of coffee and read a newspaper; the first printed newspapers; the first playing cards; the first gambling on horses; the first (indeed the only) written constitution in the history of England; the first cabinet government; the creation of the Bank of England; the first banknotes; the creation of the National Debt; the invention of the forceps to deliver babies; the invention of the pressure cooker; the first documentary histories; the introduction of opera to London; the first professional women actors; the introduction of telescopes and microscopes; the discovery of the vacuum; the creation of the scientific method of experiments, and the use of a journal to disseminate scientific knowledge.

Now this may sound as if the 17th century had one foot in the ancient and one foot in the modern. But this is not an entirely helpful way of seeing it. Because witch-persecution seemed perfectly reconcilable with all of the above to almost everyone. It’s to us that they seem incompatible. In a way an interest in witchcraft and magic and astrology not only coexisted with the scientific method; they were different elements of the same belief system. Isaac Newton believed in alchemy and angels and magic, and revolutionised modern mathematics.

No doubt there were charlatans among the astrologers in London; but there were also honest and sincere people. The song ‘Bold Astrologer’ tells of one. In the song the astrologer is visited by a young serving girl; but later the same day he might have been visited by Shakespeare, Cromwell, or Isaac Newton. Plenty of people, especially the educated, expressed scepticism about astrology, but nonetheless attended them, or bought their books.

3.

There was not only a civil war in the 1640s and 50s but also a political revolution. Men and women (mainly men) argued about the democratic franchise and property rights. In a debate held in a church in 1647, one colonel in Cromwell’s army famously said: “For really I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore … every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice [i.e. a vote] to put himself under”. People argued about the king’s prerogative and the power of parliament. They argued about whether a republic was a less corrupt, more stable and more equitable form of government than monarchy. They argued about whether Bishops should have political power (Bishops were temporarily abolished), about whether the Church of England should be disestablished.

The cavalier song ‘Hey Then Up Go We’ makes fun of puritan extremism, and at the same time speaks of the deepest anxiety that the most fundamental premises of a hierarchical society are being challenged. In some ways it was easier to satirise this than to take on the arguments face to face.

People argued about whether the law and law courts should rely on Latin and Law French, leaving uneducated people helpless in the face of the law. They argued about censorship and the freedom to read. They argued about whether the two universities were the seed-beds of hypocrisy and false learning. They argued about the abuse of power by those in high positions. They argued about parliamentary corruption.

Why would anyone be interested in the 17th century? When we look at the 17th century, we look in a mirror. It can show us ourselves, while making our own reflection seem strange and unfamiliar.

Joad Raymond

Seven Months Married

Bugbears

| 1. | Martin Said | |||

|

2.

|

Bugbears

|

|||

|

3.

|

Sir Thomas Fairfax March

|

|||

|

4.

|

Seven Months Married

|

|||

|

5.

|

Hey Then Up We Go

|

|||

|

6.

|

The Owl

|

|||

|

7.

|

The Contented

|

|||

|

8.

|

Impossibilities

|

|||

|

9.

|

Babylon Has Fallen

|

|||

|

10.

|

I Live Not Where I Love

|

|||

|

11.

|

Bold Astrolger

|

|||

|

12.

|

Old England Grown New

|

|||

|

13.

|

When The King Enjoys His Own Again

|

about

An album of songs from the English Civil Wars and seventeenth century to accompany The Violence.

I recently made an album called ‘The Violence’. It concerns itself with the East Anglian witch trials during the English Civil Wars. During my research I started to come across folk songs of the seventeenth century and Stuart era. Two such songs appear on that album: ‘When the King Enjoys His Own Again’ and ‘A Coffin for King Charles, A Crown for Cromwell and a Pit for the People’.

I didn’t seek to achieve forensic detail when finding these songs, but was keen to have a sense of the flavour of the music of the era. As a side project to the album, I started to record and adapt some of the songs, and now they are collected here.

Consider this an accompanying volume to The Violence, a scene setter, a spin off.

Although I did a fair amount of research, these are not meant to be definitive or historical readings of the songs. I have revised, edited and even rewritten in places.

Thanks to Malcolm Taylor and the library at Cecil Sharp House, and the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

Darren Hayman, February 2013.

credits

The Short Parliament are

Bill Botting

Dan Mayfield

Dave Watkins

David Tattersall

Johny Lamb

Order Bugbears on CD (PRICE INCLUDES POSTAGE AND PACKING)

Gatefold litho printed brown card sleeved complete with 16 page booklet of illustrations, lyrics and Darren’s research notes.

Pre-order Bugbears on Heavyweight 12″ vinyl

(PRICE INCLUDES POSTAGE AND PACKING)

Pressed on 180gsm heavyweight black vinyl, nestled within a luxury polylined sleeve and coming complete with a full 16 page booklet of lyrics and Darren’s research into the songs, the poems and the events that inspired the music of the time. Each song comes illustrated by a different graphic artist, including Pam Berry, Robert Rotifer, James Paterson, Rose Robbins, Frances Castle, Joe Besford, Jonny Helm, Sarah Lippett, Dan Willson and more…

The Lamenting Lady by Angela McShane (plus exclusive new Hayman recording)

One of the many things I really like about the Violence and Bugbears albums is that as well as the sound of the songs, we get words and pictures, even for the instrumental pieces!

In the seventeenth century too, if you bought a song you had heard and liked from a singer – perhaps in the street, at a market or in an alehouse or tavern – you would buy the words and pictures, printed on one side of a single sheet (known as a broadside ballad), and put it in your song collection. For example, Anthony Wood, in later life a scholar at Oxford University, began his ballad collection – of more than four hundred songs – as a young boy of 8 years old.

Incredibly, four hundred years later, ten thousand of these flimsy single-sheet songs still exist thanks to collectors like Anthony Wood. Many have been made freely available on the web by Oxford University: http://bodley24.bodley.ox.ac.uk/cgibin/acwwweng/maske.pl?db=ballads

And the University of California, Santa Barbara

I’ve been studying these songs for a long time now – in particular what we might today call ‘politopop’ – topical songs that tried to make political or religious messages. Interestingly, not only the Cavaliers used songs to get their points across. Puritans too had a way with words and music and merry morality was being sung in the towns and cities of Old England. Many broadside ballads supported parliamentarians and even Cromwell and his armies in the 1640s and 50s.

But Cavaliers won the war, and so they got to dictate the tune of history ever after. Today, the songs that are best remembered are the royalist ones – only historians like me know about the Puritan ones – while evidence shows that many ‘puritan’ songs were destroyed by their collectors after the King returned – perhaps because they were afraid that their loyalty would be questioned.

One of the longest lasting royalist songs was not in fact ‘When the King Enjoys is own again’ – though this was a popular tune. It was a song lamenting the death of Princess Elizabeth Stuart (b. 1635), sister to Charles II, in 1650, just a year after her father the King’s execution by Parliamentarian forces.

Though placed under house arrest throughout the period of the civil wars, Elizabeth was well-known as a stalwart supporter of the royalist cause and famously wrote an account of Charles I’s last meeting with his children. Among the gifts he distributed, he gave his young daughter a Bible.

Elizabeth proved a thorn in the side of Parliament, vigorously complaining about the treatment and housing she and her brothers endured. Parliament tried to break her spirit not only by moving her around but also by condemning her and her youngest brother to listen to two sermons a day. This, however, was just what she liked! Poems were published celebrating her pious scholarship and knowledge of languages, including Greek and Hebrew.

Her final move to the Isle of Wight when she was unwell proved fatal. She died just as, in London, Parliament finally agreed to let her go abroad to join her mother. She was buried in a tomb unmarked except for the initials E. S.

Almost immediately, a broadside ballad was published, entitled The Lamenting Ladies Last Farewell. This song immortalised the sad fate of this young royalist martyr.

Incredibly popular, it ran to at least six editions that same year (at least three thousand sheets). Anthony Wood’s edition was ‘signed’ with the same initials that were carved on her simple tomb ‘E.S.’.

Parliament did nothing to stop it.

Lamenting Lady’s Last Farewell to the World by Darren Hayman

(‘Lamenting Lady’ recorded by Darren Hayman)

Princess Elizabeth’s song and story continued to be popular after her brother returned, with two more editions in the 1680s and three more in the eighteenth century. By then the song came with a new woodcut image – one that portrayed the captive scholar princess with her father’s Bible.

This image continued to be influential in portraits through to the nineteenth century, at which point Queen Victoria decided that her young ancestor should be given a proper tomb in keeping with her status. Perhaps influenced by our ballad in some way, she commissioned an effigy that depicted the young princess asleep in death, with her head on her father’s book.

http://supremacyandsurvival.blogspot.co.uk/2011_12_01_archive.html

Angela McShane http://rca.academia.edu/AngelaMcShane

Record Collector Review of Bugbears

Review for Bugbears in Uncut magazine

The Pleasing Crisis of a Noun by Johny Lamb

There are several ways of approaching the noun ‘folk’, and we use it carelessly and variously. We use it with prefix when it strays too far from its perceived meaning (alt, new, weird etc), and we’ll add things to the end when it gets even further away from us (-tronica, or just -ie or -y). This aside, there are perhaps two useful routes into the noun. One being that music of unknown authorship, passed on aurally through the generations, or at least that music that survived the scrupulous moral agency of Cecil Sharp and his contemporaries, and the other, best described as a vernacular or popular music that voices the identity of a community (contemporary or otherwise). These two approaches might well contain each other, or be some way distant.

Mostly, I suppose, that what we call folk is music that sounds like folk. For the most part this works for us, but when presented with a project such as Darren’s here, we are forced to acknowledge, and to some degree reconcile the chasms of ideological, aesthetic, technical and methodological difference between various contemporary practices. And even in writing that sentence, my use of ‘us’ and ‘we’ in this text so far suddenly becomes problematic. Who is this ‘we’? Or to put it rather better by using the words of poet John Hall, ‘Who are you a we with?’ Indeed, who am I, or is Darren, a we with? ‘Bugbears’ is an album of traditional songs, but then so is ‘Broadside’ by Bellowhead, and yet, the two are not siblings. Likewise, Darren is at once doing the same thing and not the same thing as Jackie Oates. The difference, I think, lies in re/deconstruction and appropriation. It also lies in a variable take on the idea of authenticity. And thus, ultimately, the cultural resonance of any practitioner of folk music comes down to the generation and reception of meaning.

In the circles that encompass Bellowhead, Oates et al, there is much talk of authenticity, and it seems that instrumentation, arrangement, language, voice and repertoire play a big part (Bellowhead’s incongruous brass players notwithstanding). The voice is of particular interest here, where delivery will often take on the form of a regionless, quasi-pastoral timbre and ‘accent’, which you will also find rife in the singers on historical dramas from the television (think of Sharpe’s Daniel Hagman, or someone taking up a song at the end of an episode of Larkrise to Candleford). Technique and ornamentation play a large role here (instrumentally as well as in the voice). Production for these kinds of traditional players plays to those notions of transparency that manufacturers of recording equipment have been promising for decades. Things are clean and allow us to bathe in the skill, dexterity and knowledge of the players. The set of more problematic performers that might include Darren seem to understand and embrace the idea that recording, production and fidelity have compositional value in and of themselves. Furthermore, the voice is unaffected (or in the case of Birdengine, is grossly caricatured). There is an acknowledgement of historical gap, and a process of deconstruction that seems to seek a recontextualisation for this material. The appropriation of traditional song often takes an allegorical purpose, and arrangements are not faithful, nor scored within ‘the tradition’. The priorities are within different camps.

For some, authenticity might lie within knowledge of the repertoire, technique of delivery and a puritanical approach to arrangement, and for some (including me), it might lie in the acknowledgement that in this instance, there is no tangible authenticity for a living practitioner appropriating this material (in terms of its literal articulation). It is perhaps, only in acknowledging a distinct inauthenticity that we can start to ignore the term and at least do something sincere. I think the majority of traditional players, would have to concede that they have little common ground with a peasant class of community-based musician (and what community anyway?). But these things in either case, while problematizing authenticity, do not in any way effect integrity, which can be approached in terms of virtuosity or in terms of atavism, or indeed, in terms of a wilful and postmodern transhistoricism. This would become a debate of considerable length were I to introduce the idea of original song here, but fortunately for all concerned, that is not the case.

The unfixed meaning of the word folk is at once a strange thing, but also arguably a good thing. Artwork has a number of these collapsed nouns, like lyric, ballad, performance, and installation to name just four, and this allows considerable scope for interpretation. Baring in mind that of course, between and beyond the two approaches I have written about here, exists a countless number of alternative methods and histories, all of which, enticingly remain in flux. Furthermore, lest we forget, those surviving songs so variously reproduced remain, at least in part, because they are beautiful, and those significant themes like love, death, drink, fear, war and so on, continue to be of relevance beyond any tawdry argument of authenticity. It is when musicians recognise this and appropriate traditional songs, in whatever form they begin to take, that something new and something exciting can happen. At this point, the generation and reception of meaning that I mentioned earlier, becomes the focal point, and whatever aesthetic or ideological camp one falls into, surely that is a good thing?

Johny Lamb is 30 Pounds of Bone

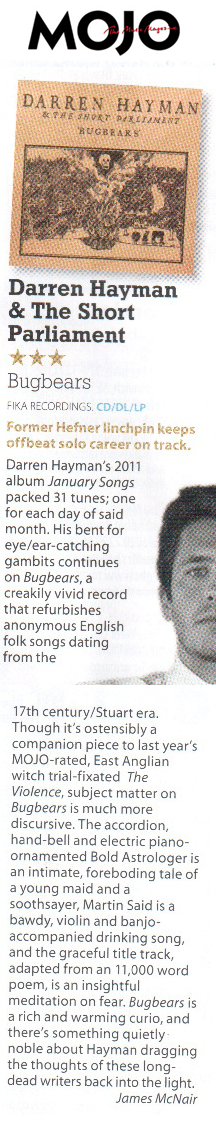

MOJO review of Bugbears

Martin Said – Video

Niklas Vestberg (Fulhäst, formerly half of Moustache Of Insanity) introduces the video for Darren’s Martin Said, from Bugbears.

Drinking…fighting…dancing

“Would you make a quick quirky cheap video for me?”

” A collection of 17th Century Songs… maybe you should choose the weirdest”

“I wasn’t thinking a full on video effort.. something quite lateral in approach. Something odd and possibly experimental”

Part of me kind of wish more music video proposals came with instructions like that – don’t make much of an effort, pick the song yourself, make it weird. Sure, the 17th Century bit was a bit of a concern. How do you even start?

In the end I picked the first track of the album. Not because it was short (but, thankfully it was) and not because I couldn’t be bothered to sit through a whole album of 17th Century songs (because I did. I listened to it all, I promise) but simply because it was my favourite track and it just resonated with me. It was probably the drinking bit, since I had being doing a fair bit of that over the past few months.

The decision to use found/public domain footage was kind of obvious. I didn’t want to film anything myself; it just didn’t seem right. So I started sifting through public domain footage on the internet, searching for clips tagged with alcoholism, drinking, parties and similar terms. Of course I wanted the clips to be interesting, but at the same time I really didn’t wanted it to be about the actual images. Bug Bears is a beautiful album, but it’s also bloody hard work and I wanted the video to reflect that. Eventually I found myself with a bunch of suitable clips and started playing around with them. Should I cut it to the beat, try to make it reflect the lyrics somehow? It just didn’t seem to work and the clips quickly became uninteresting. So I decided against all these normal conventions and started playing around with fixed clip lengths, eventually settling on one second. It seemed to work. It was long enough for the brain to start processing what was on screen, but short enough to make you work that little bit extra. I think it works. It’s unlike any other video I’ve ever done, but I’m quite pleased with the end result. Sure, it’s pretty unwatchable, but I also find it strangely appealing and almost hypnotic. Drinking, fighting, dancing, drinking, fighting, dancing.