This interview by the excellent Drunken Werewolf

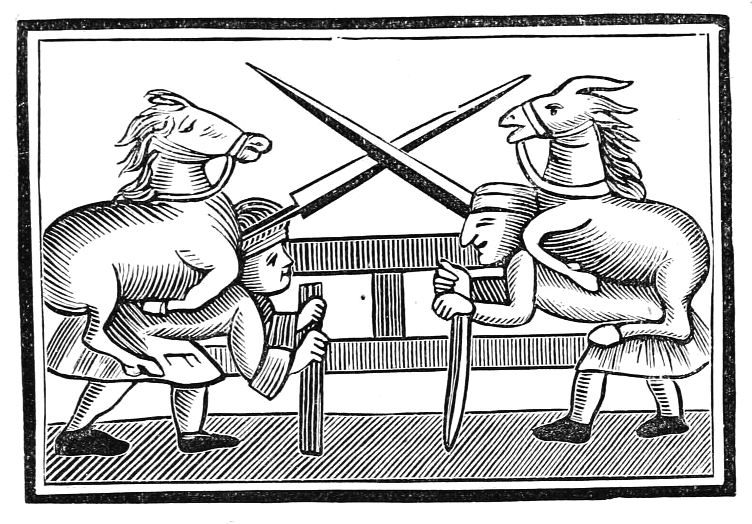

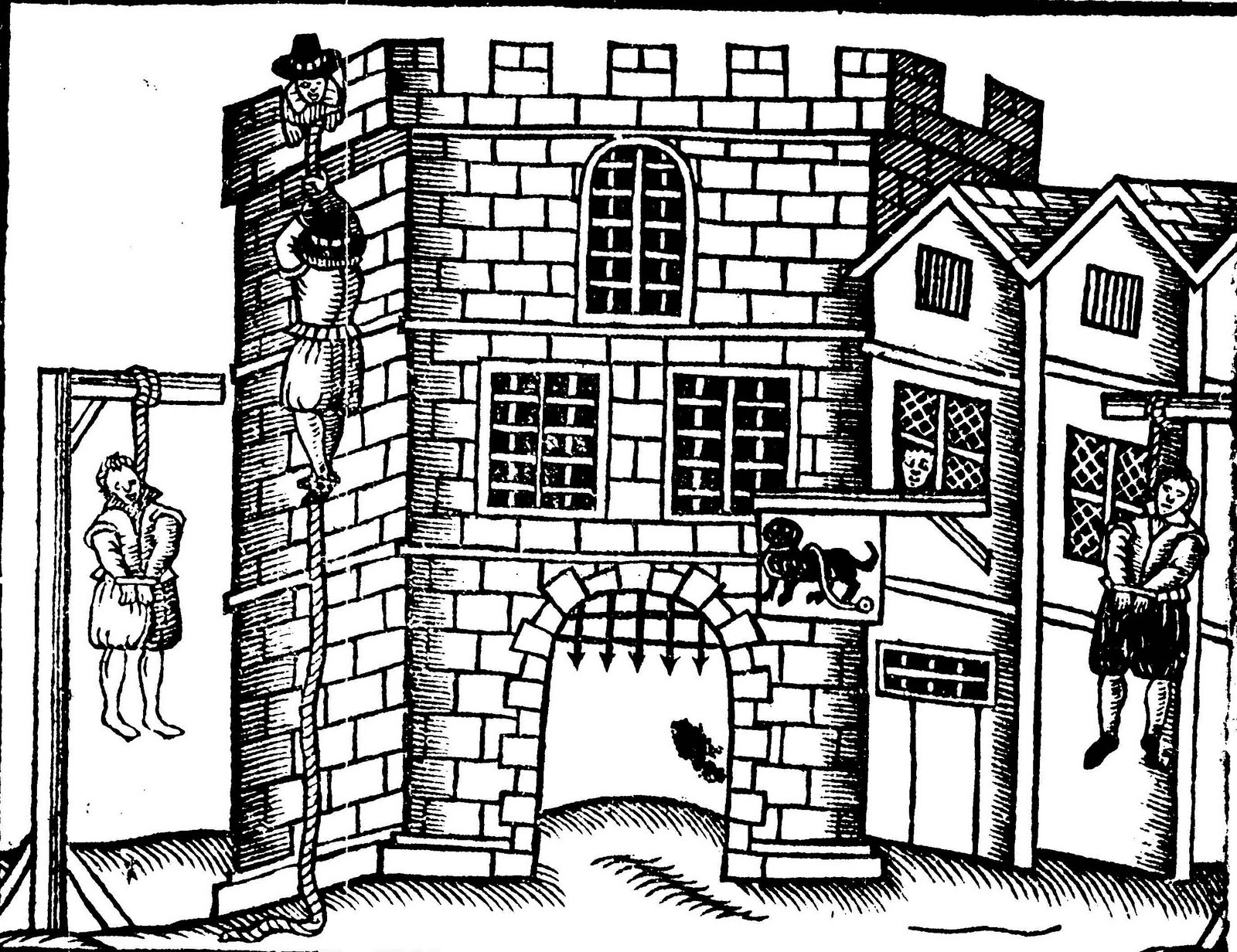

Religion, relationships, new towns and open-air swimming pools: Darren Hayman has drawn inspiration from them all. His latest album Bugbears is a collection of seventeenth century folk songs. It continues his fascination with the era which began with last year’s album The Violence chronicling the Essex witch trials and was followed by the Four Queens EP earlier this year.

In an exclusive interview, he sits down with DrunkenWerewolf’s Patrick Widdess to talk about his musical history project and why he wants to break our hearts.

So Darren, how did your fascination with English history in the 17th century begin?

I’m known for my use of contemporary language: slang, idioms, even brand names. I was doing a series of albums about Essex and I had this idea of doing something historical. I thought if I wrote about a story that happened a few centuries ago it would create hurdles in the songwriting process and make me change my approach to words.

Whilst writing The Violence I thought I should include a few folk songs of the time. I didn’t want to make the album sound 17th century but I thought I might learn something from researching them.

Interpreting and recording these songs became a separate project and album that was recorded at the same time as The Violence.

Where does the album name Bugbears come from?

The album includes a poem which was a rare rational treatise for the time. Everything else was about seeing fear and the devil in places. This poem says it’s all a lot of nonsense and to get a grip. It refers to these fears as bugbears. It seemed to capture what the whole album was about: curses and things going wrong.

You’ve changed the band name from The Long Parliament to The Short Parliament for this album. What’s the difference?

There are a few different members. The band I play with is always a little loose. There are seven or eight musicians I work with at different times. In this case I worked with those that had more of a folk leaning, particularly Dan Mayfield, the violin player. He’s from a Morris dancing family – the real deal. Not like us and Mumford and Sons who put on a folk hat when they fancy it!

It was a way to distinguish the two projects. There’s also the rump parliament which I should find a project for.

Yes, it’s a great name! How did you interpret these old songs for a modern audience?

I wasn’t trying to be slavishly accurate. Accuracy with something from as long ago as the 17th century is pretty much impossible. There’s only so much we can know about how these songs sounded.

I also didn’t want to completely reinvent the songs and say, “right, I’ll do them with a jungle beat and modulating synthesisers.” It was a case of making them sound apt without being ridiculously reverential.

So how did you change them?

First, I took lots and lots of words out. One of the fist things that strikes you about these songs is they have 18 verses. Music had a different purpose in those days. It was used to tell stories, even acted as the news. That didn’t seem palatable to a modern audience.

Also there are not many tunes. The same ones are reused repeatedly. It’s like playground or football chants where you keep reinventing the lyric to the same tune. The melody’s not important. They’re sung to taunt the other side and so have a different purpose to songs that entertain. The tunes also consisted of mostly major chords, which grates on the modern ear after a while.

So there were decisions to be made about how much you followed the earliest notated tune. There were decisions about when to adapt or shift slightly and what you could do in the name of interpretation, and what was pure invention. If I was more into folk preservation I would have had a stricter approach but I felt that was not my domain. It was about interpreting them respectfully as an indie-pop singer.

Having studied these old songs have your ideas about the role of music today changed?

Not really. I’m still just trying to write interesting songs, not give them a different use. That’s the challenge with this project; you don’t want to give a history lecture. You want it to still be a song. You want it to be about love or fear, wanting or jealousy because they’re things we all feel and that’s how you hook the listener in.

It’s made me aware of other uses songs have had in history but it’s made me more sure about what my songs are about and what I’m trying to do. Basically, I’m trying to break your heart and find more interesting ways of doing that like writing about Charles the First and Henrietta Maria.

Has the project been successful in changing your song writing style?

It has for me. It’s made me a better writer but now I’m trying to get back to writing a normal album. I’m working on 10 or 12 songs about breaking up – an everyday album about heartbreak. It’s interesting trying to do that after I’ve got used to working with pages of notes around me. I’m hoping there will be an unblockage soon and songs will come spilling out once I’ve got away from the 17th century thing.

So is the project finished now?

There’s one song that Angela McShane, head of 17th century studies at the V and A has asked me to do. I met her just this week.

I was really nervous because the research I do is just about looking for stories and a good tune: “Oh that sounds good I’ll use that!” It’s completely different to the research she’s doing looking at songs and ballads, how they’re printed and whether this lyric is more accurate than that one.

I felt like I was taking liberties with her specialist area, but actually she believes reinterpretation has always been part of the story. Her research involves going through different interpretations to unravel them. So I’m another person in a long tradition of people reinterpreting these songs, which she found interesting. So I’m doing one song, basically for her but I’m sure I’ll put it online.

Finally, what have you got planned for your forthcoming residency at The Vortex?

I sometimes tire of rock gigs and I’ve started going to jazz gigs. There are lots of things that are different aside from the music: longer sets, sitting down, largely unamplified music. I’m trying to do something like that.

Often when you see a band it’s like hearing their CV. They have to include their top O-level scores and the best bits at the end. I want it to be less like that and more “what shall we do tonight?” Each gig will be themed, but not the classic album theme. I don’t like knowing what every song’s going to be in order.

I’m theme-ing my songs into groups, and we’re planning to do 12 gigs over a year. The first is The Violence and Bugbears, then a holiday themed one for August. I’ll do a set of piano songs from different albums and we’ve thought about doing one where the first 14 ticket buyers choose the songs. Then there are the Hefner songs but not a Hefner reunion as such. We haven’t decided all of them but I’m sure the ideas will come to us.

Darren’s residency at The Vortex begins on July 11th. Bugbears is out on July 15th on Fika Recordings.