Darren Hayman and & Short Parliament’s album Bugbears is a rare thing. It’s a vision of the 17th century, and particularly the civil wars that saw Britain turned upside down; but it’s done through music that, though it’s more-or-less folky, is not at all nostalgic. Modern folk and 17th century history: it could be a little offputting. Putting aside the question of folk music, why would anyone be interested in the 17th century?

Here are three reasons, three things that everyone should know about Britain during those times:

1.

There was an information revolution. Really this began in mainland Europe with Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable type in the middle of the 15th century, which revolutionised printing. But in Britain it happened between the late 16th and 17th centuries. What happened? New communication media — cheap print — opened up new kinds of dialogues, speeding up communication, making great swathes of information that had previously been the preserve of educated elites available to a much broader public. At the same time many people worried about these new media: would they disrupt old ways of learning and traditional values? Would they undermine knowledge as much as they spread it? How could you know whether something in these new media was true?

Does any of this sound familiar?

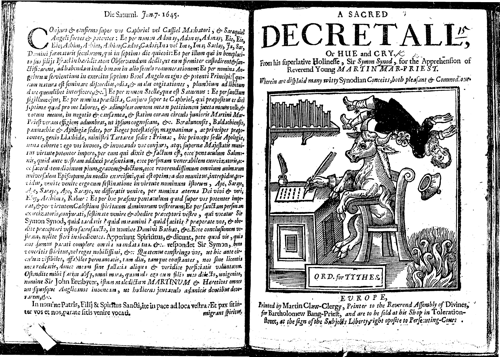

Cheap print was in some ways the equivalent of the internet. It seemed exciting and threatening at the same time. In Britain pamphlets began to appear — short books that argued about politics and religion in popular, accessible writing. They were intended to change what the reading public thought about things. Governments were concerned about the way pamphlets and pamphleteering might turn the world upside down, and from time to time tried to quash them. Pamphlets could not only be read by cobblers and tinkers: they could be written by them (actually the few who were literate). Gradually, however, politicians and governments accepted that pamphlets couldn’t be eradicated entirely, and increasingly they became part of the conduct of ordinary, everyday politics. If you wanted people to take your side, you persuaded them through print.

Pamphlets were like blogs: pithy statements of fact and opinion, arguments with invisible enemies that sewed new ideas, explorations of popular religion that were not controlled or authorised by the church. Writers didn’t care who their anonymous readers were: this was a very public, perhaps democratic, form of engagement. With a pamphlet you could try to persuade people to take your side in an already polarised conflict; or you could just throw an idea out there and see if it floated. When the civil wars began — in 1637 or 1642 depending on how you look at it — pamphlets were part of the warfare. They were paper bullets.

Meanwhile weekly newspapers (which appeared in 1641) speeded up the news, and made more news accessible to more people. In a way they created the first news cycle (at least in Britain), because readers expected weekly updates. These days we have our 24 hour news cycle. In the 17th century the news was weekly: but this in itself was quite revolutionary, and perhaps changed the way people thought of time and history, exactly as it was happening around them. This was a media revolution.

2.

As the extraordinary The Violence records at double-album length, 17th century British people believed in witches — believed in them enough to hang a few hundred poor, defenseless old women. Surely this has to be the apogee of superstition?

But there was another aspect to 17th century Britain, one that we would call ‘modern’. These are some of the things that happened in 17th century Britain: the introduction of coffee, tea and drinking chocolate; the introduction of coffee houses, where you could drink a cup of coffee and read a newspaper; the first printed newspapers; the first playing cards; the first gambling on horses; the first (indeed the only) written constitution in the history of England; the first cabinet government; the creation of the Bank of England; the first banknotes; the creation of the National Debt; the invention of the forceps to deliver babies; the invention of the pressure cooker; the first documentary histories; the introduction of opera to London; the first professional women actors; the introduction of telescopes and microscopes; the discovery of the vacuum; the creation of the scientific method of experiments, and the use of a journal to disseminate scientific knowledge.

Now this may sound as if the 17th century had one foot in the ancient and one foot in the modern. But this is not an entirely helpful way of seeing it. Because witch-persecution seemed perfectly reconcilable with all of the above to almost everyone. It’s to us that they seem incompatible. In a way an interest in witchcraft and magic and astrology not only coexisted with the scientific method; they were different elements of the same belief system. Isaac Newton believed in alchemy and angels and magic, and revolutionised modern mathematics.

No doubt there were charlatans among the astrologers in London; but there were also honest and sincere people. The song ‘Bold Astrologer’ tells of one. In the song the astrologer is visited by a young serving girl; but later the same day he might have been visited by Shakespeare, Cromwell, or Isaac Newton. Plenty of people, especially the educated, expressed scepticism about astrology, but nonetheless attended them, or bought their books.

3.

There was not only a civil war in the 1640s and 50s but also a political revolution. Men and women (mainly men) argued about the democratic franchise and property rights. In a debate held in a church in 1647, one colonel in Cromwell’s army famously said: “For really I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore … every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government; and I do think that the poorest man in England is not at all bound in a strict sense to that government that he hath not had a voice [i.e. a vote] to put himself under”. People argued about the king’s prerogative and the power of parliament. They argued about whether a republic was a less corrupt, more stable and more equitable form of government than monarchy. They argued about whether Bishops should have political power (Bishops were temporarily abolished), about whether the Church of England should be disestablished.

The cavalier song ‘Hey Then Up Go We’ makes fun of puritan extremism, and at the same time speaks of the deepest anxiety that the most fundamental premises of a hierarchical society are being challenged. In some ways it was easier to satirise this than to take on the arguments face to face.

People argued about whether the law and law courts should rely on Latin and Law French, leaving uneducated people helpless in the face of the law. They argued about censorship and the freedom to read. They argued about whether the two universities were the seed-beds of hypocrisy and false learning. They argued about the abuse of power by those in high positions. They argued about parliamentary corruption.

Why would anyone be interested in the 17th century? When we look at the 17th century, we look in a mirror. It can show us ourselves, while making our own reflection seem strange and unfamiliar.

Joad Raymond